Can Demographic Winter be Reversed?

Demographic Winter refers to the process whereby declining birthrates in a given country leads to an ageing population and thus decreasing productivity, consumption, and investment. Declining populations also mean less innovation and difficulty maintaining national security. Young people are the most productive portion of a population and should be the largest “step” on the population pyramid. As the young, productive people grow into middle age, they become the investors who drive economic growth. In time they retire, ideally in much smaller numbers than the young workers whose labor supports their pensions. Retirees are far less productive and consume far less than working age individuals.

What happens when the younger populations grow ever smaller with each generation? In time, an inverted pyramid results, or in other words: Demographic Winter. A kind of economic “nuclear winter” or dark age from which recovery is very difficult. America has one of the healthier population pyramids among developed nations today, but if nothing is done to remedy the problem, America too, will experience this catastrophic phenomenon. In the mid-14th Century, northern Europe was exposed to the black death, the great plague. England’s population declined by more than one-quarter, and there is some debate that the death toll may have been still higher, perhaps closer to one-third. It took England a century and a half to recover. It was not until the Tudor’s ascended the throne that England began to grow again and recovered its economic vitality. Needless to say, the century and a half in betwixt saw the decline of the Angevin Empire, the rise of the French nation-state, and the Wars of the Roses. A period of poverty, instability, and chaos.

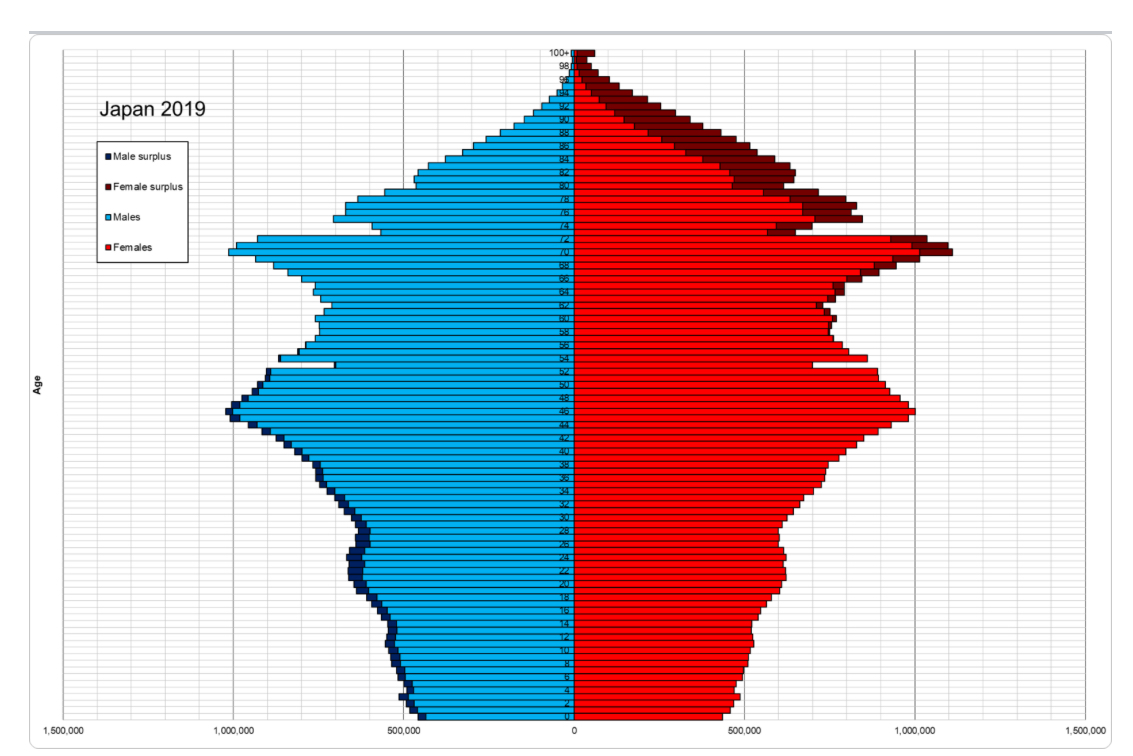

Could the process be reversed more expeditiously? This article means to propose a thought experiment on just such an effort. One of the world’s fastest ageing populations is that of Japan. Of approximately 121 million people, only 9.5% (about 11 million people slightly more men than women) are between the ages of 15 and 24. Only 12.5% of Japan’s population is under 14 (16 million people and again with a slight male surplus). In total, the population 24 and younger is 22% of the population at about 27 million people. By contrast, nearly 30% of Japan’s population is over 65 constituting about 37 million people. The 15-24 demographic is the portion of the population heading into their best childbearing years. The demographic group who must be redirected toward having large families in order to reverse the impact of demographic winter.

It is also important to note: the one factor with the greatest impact on birthrates is the desired family size of women. Nationalism and optimism about the future tend to be factors in high birthrates. Economic factors like the high cost of living and childcare also have a detrimental impact.

A Meiji Revolution in Demography

In the late 19th Century Japan underwent one of the greatest societal transformations in human history. The medieval shogunate was overthrown by modernists who desired a strong, industrial Japan. In three decades the Japanese went from a society of peasants and Samurai to a modern western-like industrial society. Girls who were forbidden to attend school lived to see their granddaughters have a basic elementary school education. If there is any society on Earth capable of making a massive demographic transformation, it would undoubtedly be the Japanese. That and the fact that their demographic situation is so dire make them the ideal Guinea pig for this thought experiment, with lessens that once drawn from this thought experiment could be applied here in the United States.

The will to undergo this transformation is the first factor. The government, societal institutions, and culture of the given society would have to be “all in” to generate the desired results. The population would have to be willing to make the sacrifices necessary. Everyone would have to believe in the cause. Let us assume that this can be achieved in Japan, how would they go about reversing their demographic woes? Japan has been making an effort to increase its birthrate which has resulted in a slight increase in births, the generation under 14 is about 5 million individuals larger than that between the ages of 15 and 24 (although the first age range is longer including a larger sample). Thus, Japan’s efforts so far have brought forth only a few million more young people. Tax benefits, extra days off, and general government incentives have thus proven insufficient; an experience shared by South Korea, Sweden, and Russia all of which have been trying to incentivize births.

First let us consider the present condition in Japan. In a vain attempt to keep up productivity, young workers are working ridiculously long hours. A 10 hour workday is fairly average and many Japanese workers work much longer hours. The government has actually tried to implement a policy of making young workers go home after their shift, to prevent them from working such long hours. Young workers in urban areas can barely afford to live. They often live in a small one-room studio apartment with a small bathroom. A study has found that 40% of Japanese people under 30 have never engaged in sexual activities with another person. The dating and relationship scene is atrocious. Many young people when interviewed simply responded that “men (or women) are just too much trouble.” Young Japanese people also feel intense social pressure to make their parents proud and to care for them, to be excellent in their field of work, and to be disciplined in life. These pressures make them feel overburdened and given their long work hours for a lack of prosperity overall, their lack of healthy relationships and personal fulfillment, this is understandable.

Turning the Corner

Redirecting the society to a healthier birthrate means liberating these youngsters from their labors, or at least most of them, and rededicating their efforts toward their families. The cost of raising a family in a city is insurmountable in most countries and especially in Japan. A demographic turnaround will thus require these young workers to move out to the countryside. It will also mean the disappearance of many women from the labor force as they focus on raising young children, especially in the early years. Once these young workers are in a rural or small town setting, they will be able to live and raise children with greater ease. Naturally, work must follow them: factories, services, and offices would have to be relocated to rural settings or home sourced. This is not impossible where the will exists. Investment in these rural jobs can be driven by government expenditure and by private entrepreneurship in accordance with such a national effort.

Let us take a moment to consider the implications for the urban environment here: the population of Japanese cities would plummet, some by more than half. The older generations would be living in the cities with fewer services and comforts with a high cost of living while the youngsters move out to the countryside. Smaller cities means less prestige, less art and culture, and a likely decline in tourism. The oldest demographic, 65 and older, will continue to grow as a percentage of the population until a new baby boom comes of age or until the largest generations of Japanese people grow old and die. What is now about 30% over the age of 65 will be more than one-third and perhaps as high as 35-40% of the population before a younger generation can succeed them. Who will care for these elderly people in their infirmity? If many of them move out to the countryside in want of services and access to younger people to care for them, the cities will be depopulated to an even greater extreme. Again, there are many sacrifices to be made here: the older generation must be willing to surrender their comfort in old age in favor of helping the younger generations raise more children.

Once this large population of youngsters moves to a rural setting and settles in, they can begin to achieve the national goal of having larger families. If those currently between 15 and 24 (first the older half of this group followed in a few years by the younger half) began having larger families, the demographic decline would begin to reverse, but extremely slowly. These young workers will be giving up life in the city, such as it is, and the opportunity to prosper through their lucrative work, in order to support the larger mission. Raising children is not easy, it requires dedication, hours of personal investment, and discipline for parent and child alike. Would these younger Japanese generations be willing to give up the ease of being single and childless for the stress of family life? While children are a blessing and raising them is fulfilling, if one is not exposed to such ideas during their upbringing, it can be difficult to encourage them to choose this path. The Japanese economy would take a significant hit from this effort. The reduced workforce, declining productivity, and the movement of jobs from the cities would all have their costs to the larger economy. Consumption by these young families would increase in time, affording the economy some benefit, but not right away.

Baby Boom by Design

So, assuming everyone has been willing to make the needed sacrifices and the transition has been made, now there are millions of young families ready to have as many children as they can. Some people are infertile. These can adopt children from those who are unfit to raise children or who die young, but they cannot produce large families. Some women will have few children even if they try to have more, they will have one or two and find themselves unable to have more. Some women will have a one or two and at some point in the process, decide that they do not want to have more. Meanwhile, some families will have six or eight children easily. Average human fertility, when nothing is done to inhibit it, seems to be around 6 children per woman.

Let’s assume this young generation is able to achieve a target average birthrate of 4 children per woman. There are currently about 11 million people between 15 and 24, assuming they can form 5 million couples and over the course of the next twenty years have an average of 4 children per woman, then there will be a baby boom of just 20 million people. Excellent for a country of 80 million, but a country of 121 million? It is also true that none of these new baby boom children will reach the workforce until about 2045, even if the younger generation started right away. They will not begin to reach their peak wealth and productivity until their early 50’s, which will begin circa 2075. To sustain this, the next generation, the 16 million under 14 today, will have to attempt to achieve the same birthrate. About 8 million couples at an average of 4 children each would be a baby boom of over 30 million. The children of the second generation of booming parents would not begin to enter the workforce before 2055 and would achieve peak wealth and productivity near the end of the century. Basically, if the Japanese could redirect the lives of its young adults and make a massive social change to bring about a baby boom, it would take the rest of the Century to achieve the desired outcomes.

It is obvious from this thought experiment that it is easier to try to correct these problems before they become so drastic, but that is when the effects of Demographic Winter have yet to be felt. If Japan had encouraged this baby boom in the 1980’s when their birthrate began to plummet, they would not be suffering a declining economy, productivity, and investment as they are today. At that time there were few people aware of the coming crisis, let alone willing to raise the alarm. Germany, likewise, faces a severe demographic decline as does most of Europe today. Russia and China are in terrible shape with Russia’s population set to halve by 2050 and China’s by 2100 if current trends hold. Russia, like Sweden, South Korea, and Japan has been trying to convince its young people to have more children. So far, none of these countries has had much success turning the corner. It would really require a massive undertaking like the one described above to reverse the effects of demographic decline.

Lessons for the United States

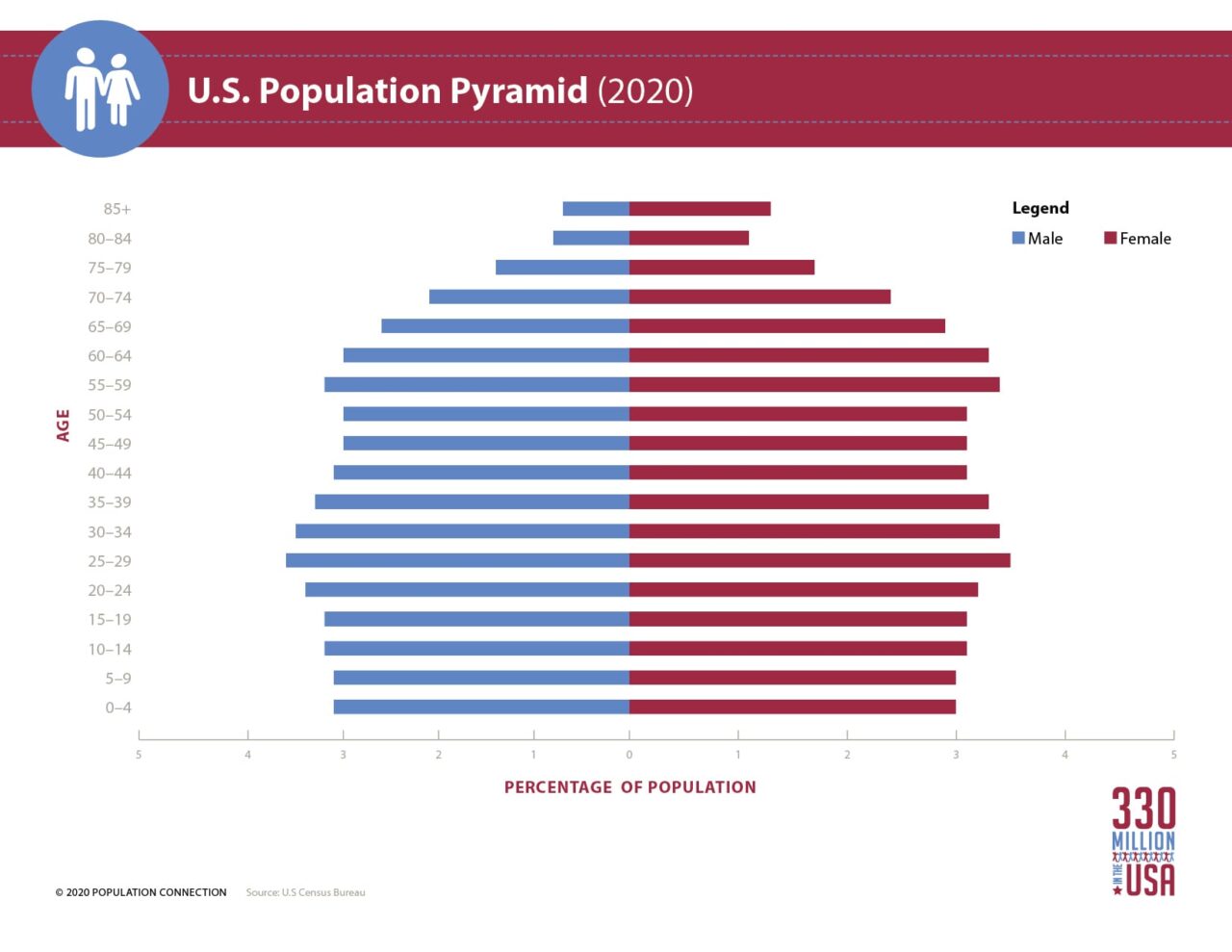

Obviously, America’s demographic situation is not as dire as those of the aforementioned countries. America’s domestic birthrate is around 1.7 (live births per woman also known as the total fertility rate). The replacement rate, the birthrate at which the population would neither grow nor decline is 2.1. In the United States nearly 18% of the population (almost 60 million) is 14 or younger and 13% is between 15 and 24 (about 45 million). While 17% of the population is 65 or older (about 58 million). If Americans continue to have children, especially if these were in healthy two-parent families (sadly at least 40% are not) then our society will be able to sustain a reasonable degree of prosperity. If our birthrate continues to decline, however, then the same disaster befalling countries like Russia and Japan will occur here too. Thankfully, America draws large numbers of immigrants who tend to have higher birthrates which affords the United States a growing population. Unfortunately, America suffers terrible illegal immigration, our legal immigration policies are not designed to benefit population growth or to foster economic growth either. Many political leaders have proposed reforms to bring in just the number of unskilled laborers, for example, to fill the jobs left unfilled by domestically born Americans while not bringing in so many that it drives wages down or floods the market with unskilled labor. Sadly, none of these reform efforts has been given serious consideration in Congress.

Imagine if our immigration policy were reformed to bring in legal immigrants in numbers beneficial to the economy while also prioritizing population growth. Bringing in young families who possess necessary skills or education in numbers that benefit the economy and the population numbers. Immigration is one area in which policy can influence population growth. What could the federal government and states do to encourage healthy families and population growth among domestic Americans? It must be noted that domestic Americans includes all demographics in America, including all racial and ethnic groups. For some strange reason, making reference to increasing domestic birthrates is often followed by claims of racial bias. Increasing the birthrate of all Americans of all kinds is the goal.

Welfare policies discourage two-parent families that are known to be the healthiest for the children. Healthy two-parent families lead to better educational outcomes, and a lower likelihood of living in poverty either as a child or later as an adult. Imagine a welfare system and social safety net designed to encourage healthy two-parent families. If greater benefits were offered to two-parent families wherein one parent is working while benefits were slowly reduced to single family households, we might see surprising changes for the poorest demographics in America. Declining crime, increasing education, and improved economic opportunity.

Finally, a general cultural reform must be attempted aimed at encouraging healthy two-parent families. Work hours and circumstances must be adjusted to benefit mothers with young children. How about allowing women to leave the workforce for 10-15 years to raise young children then easing them back into the workforce seamlessly? Discouraging negative messages about parenthood and instilling in people an ideal of wholesome family lives? It sounds like what happens when government stops promoting strange ideas like the LGBTQ agenda and instead lets people make up their own minds about life and morality. Our society would see significant benefits from reducing the harmful anti-family message in our society and promoting a pro-family agenda instead.

Culture impacts family size in other ways. Vehicles are generally made to hold 4 or 5 people. Minivans hold 7. If one wishes to have a larger family they are forced either to travel in multiple vehicles or to purchase a larger vehicle capable of carrying the entire family. Housing is also a challenge: apartments are typically 1 or 2 bedroom and few have 3. Even so, no more than six people can occupy a 3 bedroom apartment in the United States thanks to HUD regulations. Our entire culture is also built around convenience and spontaneity, whereas parents need to plan outings.. Increasingly, children just do not play into our culture’s plans let alone larger numbers of them.

Encouraging young people to move out to the countryside and start families and then moving the jobs to them is a monumental task, but not an impossible one. Making the attempt with any degree of success will ensure American prosperity for generations to come. If this is not our path, then America will soon face the same decline that Japan and many other societies are struggling with. Once a society goes too far down the path of demographic winter, recovery becomes much more difficult. Better a stitch in time.

About the Author

Isaac Kight is a Jewish conservative commentator. Isaac and his wife live in the Mid-West and have 7 children.