Netanyahu Wins Again Amid Israel’s Ongoing Political Impasse

The recent Israeli election came to a predictable result: for the third time Prime Minister Benyamin “Bibi” Netanyahu won an election and may still prove unable to form a government. Is Israel in store for a fourth national election? What has broken down in Israel’s electoral system that it has come to this?

The first and greatest of Israel’s political problems is a personal one: the opposition and the Israeli government establishment do not like Prime Minister (PM) Bibi Netanyahu. The PM has held office longer than any other Prime Minister in Israeli history. It is uncommon for a PM to make it longer than four or five years. Even those who outlast that brief average do not last much longer. Only Israel’s founder David Ben Gurion held the office for an elongated stint. Until Bibi broke his record. Israel is thus in uncharted waters. Netanyahu was Prime Minister from 1996 through 1999 when he lost a direct election of the PM due in part to a sex scandal. He rehabilitated his career in Ariel Sharon’s government as Finance Minister then returned to the PM’s office in 2009 after a 10-year hiatus. He has been Israel’s leader for the last eleven years and is seeking to put together just one more four year term.

The Israeli establishment has other plans. The Attorney General has led numerous never-ending investigations into purported corruption. This led to the filing of charges late last year conveniently timed to try to end the Prime Minister’s career. The charges were not filed for some time because the evidence is weak and circumstantial and Bibi is unlikely to be convicted. A trial of these crimes is essentially a waste of time. Under Israeli law, however, it is possible that Netanyahu could be ousted from office while he goes to trial. In the political world even a brief absence from office can be lethal as competitors maneuvre into places of power to unseat their erstwhile rivals. Meanwhile, a political coalition has formed of parties opposed to the Prime Minister who are unwilling to join his coalition partners to form a government. In Israel’s proportional representation system parties win seats equal to their percentage of the total number of votes. Read my analysis of Israel’s previous election for more detail.

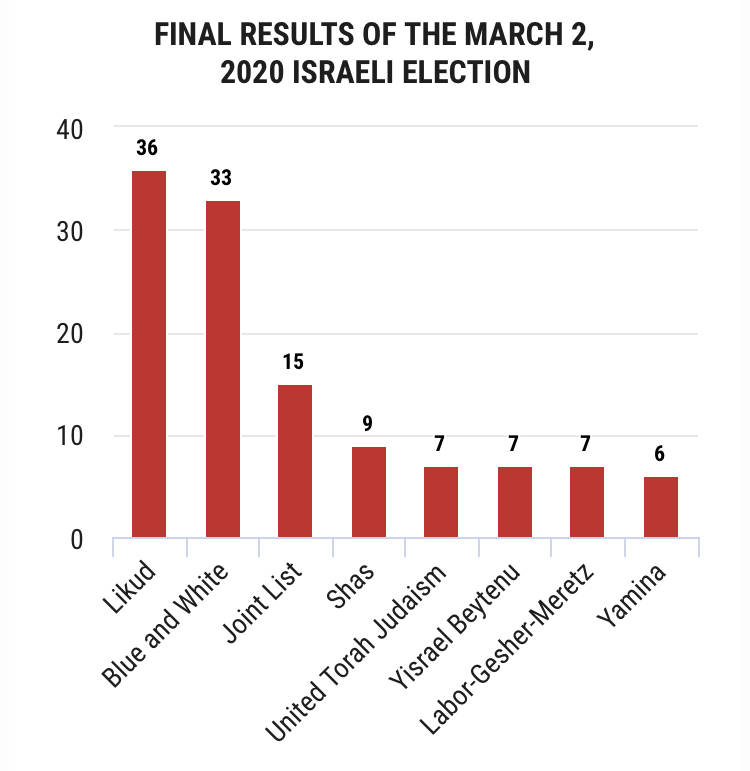

Thus, even as Netanyahu has easily won more votes and more seats for his parliamentary bloc in three successive elections, he is unable to complete the win by forming a stable coalition of parties because his allies do not total up to a majority of the total number of seats. In this most recent election, Netanyahu’s Likud Party and his supporting parties won 58 seats out of 120 total, just three seats shy of the 61 needed to elect a government. In parliamentary systems the parliament is essentially an electoral college that elects a Prime Minister to lead the government. Unlike America’s Electoral College that votes once and then dissolves, parliament continues to sit and has the power to remove the Prime Minister by a vote of no confidence. Thus, the Prime Minister must maintain the real time support of a majority of the members of parliament.

Is Bibi the Problem?

The Blue and White Party (Kahol – Lavan) and their Labor allies, along with Avigdor Liberman’s Yisrael Beteinu Party, have now introduced legislation that would require Netanyahu to resign due to his legal troubles. Curiously, after losing an election these leaders have sought to overturn the results with legal maneuvres. Sound familiar? This tactic has been tried with little success in Washington DC. Would Bibi’s resignation, his departure from the political situation, really resolve the crisis? That is a tricky question. There is no obvious successor to Bibi in the Likud Party. This, in part due to the fact that Netanyahu himself has run off all of his competitors. Thus, any successor would find themselves in a weak position leading a Likud Party haunted by the ghost of Bibi past. The party institutions are still controlled by Bibi himself and it would take time to wrest the party from his yoke. Essentially, Bibi’s departure would then hand the onus of leadership to Benny Gantz and the Blue and White Party.

Blue and White is a young party whose leaders are untested. It is unlikely that they would be able to form a government even in this situation but they would be the more organized and better led faction if Bibi resigned. Still, they and their natural allies the far-left Labor Party have only 40 seats, twenty-one shy of a majority. Even if they added the centre-right Yisrael Beteinu Party and the far-right Yamina (Right) Party they would still fall eight seats short of a majority. The Arab parties do not join governing coalitions and the ultra-orthodox religious parties, who have sixteen seats between them will not join a coalition with Blue and White. One of the party leaders, Yair Lapid like his father before him, has made a career of opposing the special privileges of the ultra-orthodox. Thus there is no pathway to a coalition led by Blue and White. Nevertheless, any coalition made up of parties allied to Blue and White and centre-right parties, even if they could achieve a majority, would be weak and fractious. The very first major political crisis would bring down the government forcing, you might have guessed, yet another election.

If Netanyahu does resign, it is difficult to imagine Blue and White forming a unity coalition with Likud under a different leader. This would still deny the top office to Benny Gantz for at least half of the term, if precedent holds, the first two years. The Likud Party membership generally leans to Netanyahu’s right, would the party membership accept a new leader who looks weak and centrist? A unity government is the path that Israeli President Reuven “Ruby” Rivlin is backing, as this is easiest way out of the political deadlock, but the parties do not want to work together, especially so long as Netanyahu will continue as Prime Minister. Netanyahu has also called for an emergency unity government as a short-term measure to combat the spread of the Wuhan Virus (Corona Virus/COVID-19).

leader of Yisrael Beteinu (Israel is Our Home)

So, it seems the crisis cannot be resolved just by Bibi’s departure. The easiest way out would be for Avigdor Liberman to drop his objections to Bibi and for his Yisrael Beteinu Party to join the government, which would see stable leadership for the next four years. Having staked his reputation on ridding the country of Bibi, Liberman is unlikely to reverse course. So the two political solutions are unlikely and Bibi’s departure equally unlikely; the constitutional crisis will continue.

Israel’s Electoral System Breakdown

When Israel was founded a proportionally elected body was chosen in order to write a constitution. The theory was that the proportional system, in which voters vote for parties that earn seats according to their percentage of the vote, would lead to the election of parties representing every demographic and every sector of Israeli society. This was thought to be an ideal way to empanel a body to draft a permanent constitution. That constitutional assembly, however, never did actually draft a constitution. Israel developed a “Basic Law” under which this proportional system was perpetuated until today. In the past, when a deadlock was reached somehow the parties would find a way to compromise to form a government, even if only for a few years. Following the infamous 1984 election wherein neither major party had a pathway to form a governing coalition, the two largest parties chose to form a “unity” government together instead. The left party (Alignment) led by Shimon Peres had won the largest number of seats so Peres sat as Prime Minister for the first two years and Likud’s Yitzack Shamir then resumed office as PM for the remaining two years. Israel had never come to a situation wherein no government could be formed and a second election had to be held; until 2019.

Centre-left opposition leader Yair Lapid merged his Yesh Atid Party (There is a Future) represented by the colour blue with former General Benny Gantz’ Resolution Party represented by the colour white to form the “Blue and White Party.” Together with the old leftwing Labor Party (which used to be called Alignment), they sought to defeat Netanyahu and form a government led by these two men. In April of 2019 the regularly scheduled elections saw Bibi and his partners win the largest bloc of seats, but fall short of a majority. Netanyahu and his allies had won 56 seats but not the 61 seats that constitute a majority. The nationalist but otherwise centre-right Yisrael Beteinu (Israel is Our Home) Party led by Avigdor Liberman held five seats and could have joined the coalition making up a majoirty. This party represents largely secular and nationalist Russian post-Cold War immigrants to Israel. Liberman refused to join the government and this brought on a second election in September of 2019. In the September election Blue and White won the most seats but they and their allies fell far short of a majority with 39 seats while Netanyahu and his allies won 55 seats. Again, no government could be formed.

Part of the problem for the Israeli centre-left is that the minority Israeli Arabs have a large coalition of parties called the Joint List and they earned ten seats in April, thirteen in September, and fifteen seats in the most recent election. The Arab parties refuse to sit in any Israeli governing coalition right or left, hampering efforts for the Israeli left to win elections.

Again, after two elections neither Netanyahu nor Gantz were able to form a government together or separately. Israel had never held a second election after failing to form a government. Now, Israel has been forced into a third election. A second way in which Israel is in uncharted political territory. There is no precedent within Israel’s existing electoral system for addressing this kind of impasse. In the recent election held in early March 2020, Netanyahu and his allies won 58 seats falling just shy a majority. Thus, the impasse continues. Bibi gained popularity by acting quickly in support of the peace plan put forth by the Trump Administration, which has been a great friend to Israel and the Jewish People.

In this difficult time in which Israel’s future and the prospect of a Palestinian state hang in the balance, Israel needs experienced leadership. In this writer’s opinion, and that of the greater number of Israeli voters, that means Bibi Netanyahu should continue in office. There is a strong cabal that seeks his ouster and is willing to stop at nothing to achieve that end. They have driven Israel to three elections and a year of political uncertainty just to grind their petty personal ax.

As the political crisis intensifies Netanyahu refuses to step down and why should he? He and his allies have won all three consecutive elections within a year, coming in far ahead of their opponents. Gantz and the Blue and White Party refuse to compromise to form a Unity government, although Bibi has not exactly been willing to make sweeping compromises himself. Now, it is possible a fourth election may take place. If this is the case, Israel must consider constitutional reform before conducting a new election.

Constitutional Reform is Necessary to Resolve the Impasse

The problem here is Israel’s Multi-Party Proportional system (MPP) in which voters can choose small parties with a narrow set of political interests. This is in stark contrast to Majoritarian Parliamentary systems like those of the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. In these countries, the parliament is elected from single-member geographic constituencies where the candidate who earns the most votes wins (the so-called “first past the post” system). In these elections, similar to the elections for the House of Representatives and state legislatures in the United States, voters must choose larger political parties who represent a broad cross-section of society. In majoritarian systems large parties have a greater likelihood of earning a majority of seats outright, ergo the name majoritarian.

These larger majority parties work like standing coalitions of various interest groups each of whom must compromise in the setting of a national agenda. In the United States, for example, the two major parties represent broad coalitions of various political interests. Environmentalists and organized labor work together in the Democratic Party. Christian Conservatives and populist working class voters work together in the Republican Party, for example. In a proportional system like Israel’s, each of these groups would have their own smaller party that serves their narrow interests. In the past a truly majoritarian system seemed infeasible in Israel.

With so many varied communities packed into a small country drawing geographic constituencies could be a chore. An ultra-orthodox neighborhood would not mesh well with one made up of retired eastern Europeans. Yet, among the suburbs of Tel Aviv, B’nei B’rak and Ramat Gan are right next to one another. There is also a middle ground betwixt the two systems, the choice is not so black and white as MPP versus Majoritarian. The German parliament, the Bundestag (Federal Diet), is elected by a combination of geographic constituencies, called mandates, and proportionally apportioned seats. As a result, Germany has typically had a few larger parties who have generally gone back and forth leading the government. If Israel chose to alter its electoral system it could choose the German model which would encourage voters to choose larger parties with more varied interests and retain some vestiges of its current proportional system.

In recent years as the threshold for earning seats in parliament as risen slowly from 1% to 3.25% (the minimum percentage a party must earn to win seats) voters have slowly begun to vote for larger and larger parties. The Arab minority is concerned that their several parties might not earn any seats at all, leaving them unrepresented. To prevent this, these parties have started running together as part of a larger list so the voters can pool their votes to make sure they win seats. A mix of geographic mandates and proportional seats would still ensure minorities are represented. The ultra-orthodox, Arabs, and other interest groups could win mandates in districts where their constituents have larger numbers as well as proportional seats. Yet, the larger parties would win more seats and have a greater likelihood of being able to form a government.

Neil Regachevsky of Tablet Magazine also argues for electoral reform:

“The chief advantage of proportional representation seems to be the warm feeling of every voter that their vote matters regardless of whether their neighbors lean a very different way. Yet in practice, PR typically leads to weak, chaotic, or nonexisting governments, as has often occurred in Germany, Italy, and now Israel.”

“Statesmen ranging from Alexander Hamilton to David Ben-Gurion have recognized that political crises, dangerous as they are, can sometimes afford the opportunity for necessary revolution or reform. The current paralysis in Israel demonstrates that PR has become a clear danger to the long-term health of Israel. Now is the time to push for such reforms.”

If a fourth election is to take place, it cannot take place under the current election system. If the political impasse holds firm, only a change in the electoral system can break the deadlock. The electoral system must be reformed. This may prove difficult since such reforms could very well help Bibi Netanyahu continue in office or help his opponents finally unseat him. It is a gamble, but one worth staking. The German electoral model would offer greater political stability in the future and would likely prevent this same set of troubling circumstances from recurring. It is possible for Benny Gantz and the Blue and White Party to win an election under such an election system as much as it is possible for Bibi Netanyahu and Likud to win. If the one side is doomed to defeat it will be as a result of the choice of the voters, not an ongoing impasse due to the intricacies of the structure.