Reforming the Supreme Court

It is a curious phenomenon that the left is always eager to propose reforms to institutions when they lose control of them. Those institutions they control are sacrosanct and cannot be touched. For about five decades Americans have been held hostage to a far-left social agenda advanced by the Supreme Court (SCOTUS). During those years as the left controlled the court, at times with no more than just five justices, the Democrats and the left would hear nothing of any proposal to reform the SCOTUS. Now that they will have a small minority on the court, they are suddenly interested in reform. While this is typical of the American left, there may be an opportunity to contemplate SCOTUS reform. Any reform that might prevent the prospect of another half century of undemocratic far-left rule over social policy would be worth considering.

The Supreme Court

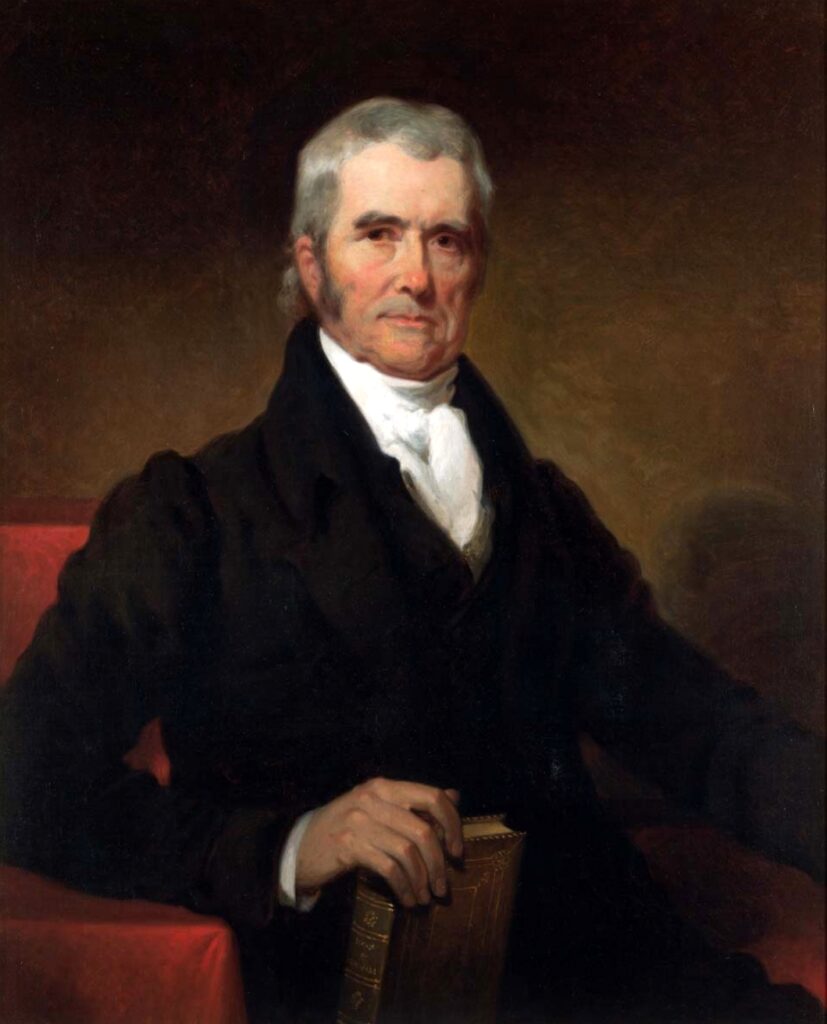

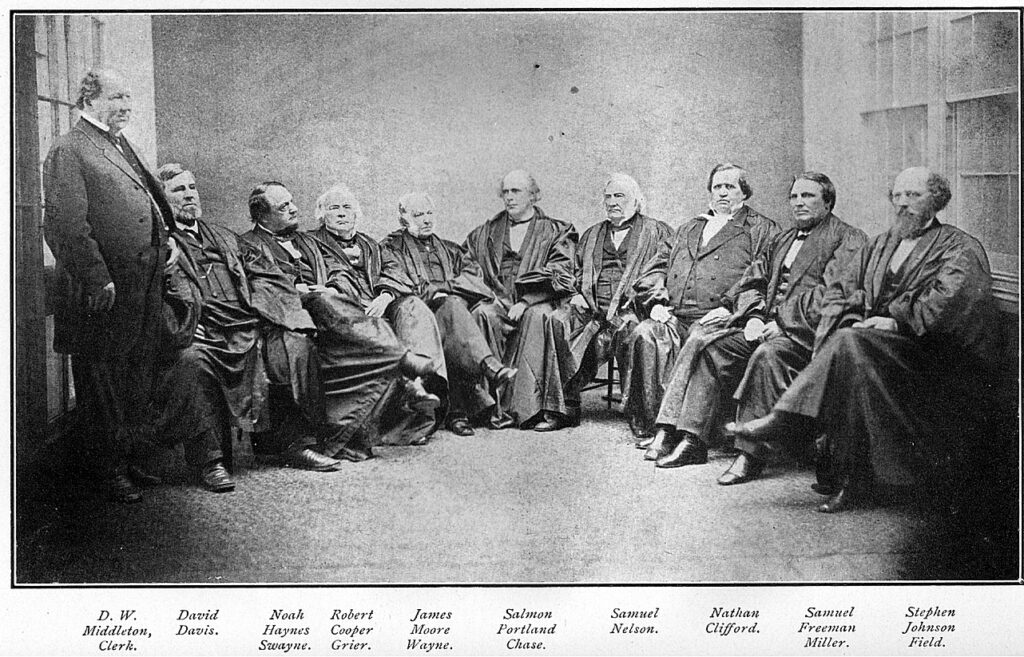

The Constitution is uniquely vague on the Supreme Court. The Framers were certain that there should be an independent judiciary as a coequal branch of government. How precisely it would work and what precisely would be its role in the government were not immediately clear. The Constitution provides no specific number of justices for this court and grants the justices a term which lasts “during good behavior;” a fancy way of saying for life. The Congress first established the court at six total justices in 1789. John Adams and a lame duck Federalist Congress lowered the number of seats to five in the Judiciary Act of 1801 in order to limit incoming President Thomas Jefferson’s influence on the court. Jefferson’s party, the Democratic Republicans, quickly repealed the act and restored the court to six justices. In 1807 the same party added a seventh justice. President Andrew Jackson packed the court by adding two more seats.

During the Civil War there was briefly a tenth justice. In 1866 Congress again restored the total to seven. President Ulysses S. Grant later signed a law restoring the court to nine justices in 1869. Since then the total has remained at nine. In 1938 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) briefly pressed to add six more seats to the court after several New Deal programs were struck down by the court. He backed down in the face of overwhelming popular opposition to the move (an obvious power grab). Then Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and the legendary liberal Associate Justice Louis Brandeis (the SCOTUS’ first Jewish justice) both vociferously opposed the move. Vacancies on the court soon resolved the matter in FDR’s favor and the issue was dropped.

Role of the Supreme Court

The problem with the court, unfortunately, has not so much to do with its number or the length of the terms of its justices but with its role within the federal government. The original role of the court was likewise left vague by the Constitution. Article III offers some powers to the court: it is the court of final appeal and it can exercise original jurisdiction over certain types of cases. But not much else was stated. Alexander Hamilton seems to have been under the impression that there would be judicial review (see Federalist No. 78) and he did not believe this to have been a controversy among the other Framers. That the doctrine of Judicial review would be established was not, however, a fact or a guarantee at the time.

It was not until the famous Marbury v Madison opinion issued in 1803 that the court asserted its power of judicial review, the power to strike down the laws of Congress and actions of the President when those were deemed unconstitutional. In perhaps the most infamous case involving the court, the court in Cherokee Nation v Georgia decided against the state of Georgia’s plan to relocate the Cherokee, Creek, and other tribes by force to the Indian Territories (the future Oklahoma). President Jackson supported the removal and moved forward with it anyway. Jackson said famously: [Chief Justice] “Mr. Marshall has made his decision. Now let him enforce it.” The result was the heartbreaking episode of the Trail of Tears; a black stain on America’s soul.

The 20th Century saw the rise of a more powerful federal government wherein the courts became a powerful force. The doctrine of judicial supremacy has become a part and parcel of American political and legal culture. This was by no means a certainty, given that the legislative and executive branches each have a role in interpreting the Constitution, especially the former, and the states themselves are supposed to hold broad discretion at lawmaking and policy making in their jurisdictions. Sadly, the court was permitted to bulldoze over those barriers and establish itself as the supreme authority over the constitution and law at every level.

In the latter years of the 20th Century, especially following the Roe v Wade opinion, the court has driven an agenda that has seen it interfere with lawmaking and healthcare policy in every state. The court has been used by the left to make policies that have never held the support of an American majority. “Abortion on demand, without restriction” has always gone against the public weal, whereas a majority of Americans desire at least some regulation of the practice, especially state and local health regulations and sanitation codes. A majority now support the heartbeat ban that would see abortion prohibited after about the first six weeks. On this and other issues the left has used the court to enact policies they know no elected official could ever enact, since they would be quickly turned out of office. A group of unelected justices accountable to no one and serving life terms? That is an excellent institution from which to dictate new laws that can never be overruled.

Reform Proposals

Given the complexities of the law in modern times and the advantages of greater diversity on the court (I mean diversity of legal background, expertise, and area of practice), a larger court could be advantageous. All the more so if the court would constrain itself to addressing the application of the law instead of engaging in judicial activism by creating new laws. Imagine, for example, a SCOTUS of 15 justices where seats were doled out, by tradition if not necessarily by law, to justices of varied backgrounds. If no fewer than three justices were former justices of state supreme courts, six former justices of the federal appellate courts, three justices with experience as law professors, and among these and the remainder it would be desirable to have justices with legal expertise in varied areas of practice: patent law, family law, contract law, corporate law, real estate law, securities law, and so forth.

Just to make the heads of the woke crowd explode all the faster, if President Trump is reelected he could propose such a reform of the court. In 2021 Congress could add six more justices to the court and President Trump would nominate the new justices, establishing a 12-3 majority of right-leaning justices! (Yes, this is a joke). All jokes aside, it is worth contemplating an expanded court and addressing the length of the terms of such justices. Unlike a change in the number of total justices, a change in the length of the term would require a constitutional amendment. This could be as simple as a single section allowing Congress to set a length of term for justices of the Supreme Court.

As justices appointed to life terms depart the court, new justices appointed to the court could have terms staggered to permit one seat to be vacant every year or every second year. Thus, each year or two a new justice would be appointed to the court. In theory, an existing justice could be reappointed if the President at the time the justice’s term expired chose to do so. An 18-year term would provide for one justice of a nine member court to be appointed every second year, thus every presidential term would appoint two justices. Any other vacancies that might arise would be filled until the regular term expires. A fifteen-member court with a 15-year term would mean an annual appointment or four justices per presidential term.

Reform Versus Court Packing

Restoring the court to its proper, constitutional role is the highest priority of the American people. Not to drive a far right or far left agenda, but to do the work the court is intended to do. To make certain laws are written correctly and properly applied, that judicial procedure is judicious and rightly observed, and that the expressly written constitutional rights of the American people are not abridged. To facilitate that end, and to prevent the court from returning to its tyrannical past, a long-term national dialogue exploring potential reforms to the court along the lines discussed above would be valuable. An underhanded effort by the left to restore their activist hegemony by packing the court would be most unwelcome.