Student Loan Crisis: Predatory Lending at its Worst

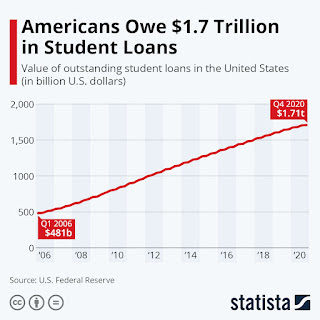

Right now, total student debt in the US stands at approximately 1.75 trillion dollars, with 42.9 million Americans owing an average of $36,510 each (source). Total US personal debt, including student loans, is about $15.24T, with almost 10.5T of that being mortgages (source). That means that student loans make up 11.4% of total personal debt in the US and over a third of personal, non-mortgage debt. The vast majority of student debt was issued by the federal government, and almost all borrowers are students, not parents, over the last few decades (source). The politicians and talking heads have decided that student loans are a black and white issue: either you are for carte blanche loan forgiveness or you oppose any leniency or aid whatsoever. It’s a manipulate approach, calculated to herd people into emotional reactions and to ignore important factors.

In this particular case, all the attention is being placed on the question of what to do about students and former students–what accommodations should they receive if they struggle to repay their debt, if any–and the character of those students, but very little energy has been spent on what should be done about lenders or universities, who benefit very directly from the current situation. Politically, the issue has been divided between one camp that argues that students who can’t repay are victims and another camp that argues those students were reckless, irresponsible, and malicious. The thing about loans is that they are a kind of contract. All contracts have multiple parties who come together to agree to do certain things for each other and to abide by certain rules. A contract is supposed to put the parties, who may be very unequal to each other (such as contracts between a recent high school grad and the federal government), on a relatively level playing field when it comes to their partnership and to the law. With student debt, the insistence on only discussing debt forgiveness and whether that’s a reasonable form of accommodation for the unfortunate or a form of theft or fraud perpetrated by borrowers, removes the lenders (mostly, the federal government) and universities from the debate, effectively placing them above reproach, while patronizing struggling borrowers as hopelessly irresponsible at best, either due to immaturity or intent to defraud. In short, it deliberately ignores the purpose of a contract and the question of whether all parties are acting in good faith.

When a bank sells a loan, it is required to do its due diligence to ensure that the loan is a good investment–that the debt will be repaid in full, on time, and with the agreed upon interest. Not only does the law require these precautions, but the bank’s investors will only continue to invest if they believe the bank won’t make stupid decisions with their investments. Banks that regularly issue bad loans generally don’t prosper, and they lose the confidence of their investors. After all, an investment is a type of loan, and investors want to be repaid in full, on time, and with interest. With student loans there are very few such safeguards. Since most student loans are issued by the federal government, the “investors” are taxpayers, both individuals and businesses, and they cannot simply withhold their investments (taxes) if they lose faith in the institution. Since both major parties are equally invested in the status quo ante with regards to student loans, voting doesn’t change anything either.

Since the lending institution is also the entity that writes the rules for lending, it has excused itself from many of the due diligence requirements that normally apply to lending. With most loans, if the borrower cannot repay the money according to the loan terms, the borrower has the option to renegotiate their debt, missed payments are reported on the borrower’s credit, loan collateral (if there is any) will be seized by the lender, the borrower will struggle to access other loans or reasonable interest rates for several years, the borrower can settle the debt or declare bankruptcy, the bank will charge off the loan by selling it to a collections agency and writing off the loss on their taxes, and/or the bank might sue the borrower to settle the debt.

Student debts cannot be settled. They cannot be included in bankruptcy. In some cases, they don’t even extinguish if the borrower dies. If a borrower tries to default, their credit will suffer, but they will still be forced to repay in full. Borrowers do have the option to renegotiate their repayment terms in the form of various programs that ease repayment terms, such as a 10-year plan, whereby borrowers make reduced payments and receive partial loan forgiveness if they work for a government institution, or income based repayment programs, in which borrowers pay based on their income for twenty years and whatever debt remains at the end of the term is supposed to be forgiven. However, it’s come out in recent years that most participants in those programs aren’t actually eligible for any debt forgiveness, regardless of what they were led to believe when they entered those programs (source and source). Recent actions by the current administration have forgiven or partially forgiven some debtors, but those orders do not fix the underlying problems that led to people not receiving what they believed their repayment program promised. The administration has also recently withdrawn from a lawsuit over the inclusion of student debt in bankruptcies, saying that it is reexamining bankruptcy policy (source).

Since the borrowers are students, they generally have limited income and assets and a short credit history, if any. Some don’t even have their own bank accounts yet, meaning that the usual means of due diligence can’t apply to these loans. Some borrowers have their parents cosign their loans, making their student loans more akin to other forms of debt, but for the most part, student loans are best compared to small business loans. With small business loans, the borrower’s income, assets, and credit are important, but the future viability of the business is the bank’s primary focus. Does the borrower have a reasonable plan and realistic expectations of their business? Is the business likely to prosper? Does or will the business have assets that can serve as collateral if it fails? For students, the question is not whether they are good borrowers now, but whether they will be able to repay their debts once their education is complete. Unfortunately, the current student loan approval process doesn’t look at that.

(source)

At the time when students borrow, lenders don’t take the reputation (beyond accreditation), graduation rate, or post-graduation employment rate of the school involved or the desirability of the student’s intended major into account, meaning that the student’s future ability to repay the debt plays only minimally into the decision to lend. No consideration is given as to how many college educated members of the workforce are needed, either, meaning that the overall value of university degrees on the job market decreases as the number of degree holders increases. And the ease of access to student loans has resulted in the astronomic increases in tuition and other university costs over the last few decades, an increase that has far out-paced, not only inflation, but the pressures of supply and demand. The amount the federal government is willing to lend per year creates a price floor on tuition. Universities also place a lot of undue pressure on students to continue borrowing.

While some students are undoubtedly foolish, that does not change the fact that the universities and lenders (especially the federal government) have not acted in good faith, despite their positions of power over the students with whom they enter contracts. It also does not change the fact that people who act foolishly in taking out other kinds of loans are afforded protections and relief that student borrowers are not.

Back in 2008, the mortgage crisis involved a lot of banks, spurred on by federal regulations, selling high-interest mortgages to people who could not qualify for or afford traditional home loans. The people who bought those mortgages knew they were poor candidates for home ownership. They knew they would struggle to repay. If they could have qualified for a traditional mortgage, they wouldn’t have signed on to a more expensive loan. Some worked with realtors to cheat the lending system, and they knew it. Many took out high-interest mortgages in good faith, banking on their ability to refinance after a year or two to a traditional, lower-interest mortgage they could more easily repay. They simply didn’t realize that real estate prices were about to peak, and their mortgages would be upside down when they were ready to refinance. Many of these borrowers lost their homes, and many had to declare bankruptcy.

No one would argue that they got off scot free for their failure to see through their home loans. And no one would argue these borrowers were entirely innocent victims of corporate scheming. The bad decisions of those borrowers (which often did not seem like bad or excessively risky decisions at the time they made them) did not excuse the lenders from choosing to engage in predatory lending practices. Moreover, it did not excuse the federal government from creating a regulatory environment that encouraged predatory lending. While the borrowers suffered the consequences of their decisions and circumstances, so did many banks and brokerages for their choices and bad faith. And yes, the people and businesses whose investments funded those bad loans also suffered losses as a result of making poor investments.

Right now, the federal government sustains a huge bureaucracy that exists solely to service student loans and interact with borrowers as they manage their repayment (source). A huge percentage of those borrowers will never have the income to repay those debts they recertify every year. More bureaucracy exists to sell new loans to new students. Since the federal debt is currently approximately $30T (source), it’s also worth considering that all federally held student debt and all money paid to maintain these bureaucracies is borrowed money, not real money actually contributed by investors (taxpayers). We are talking about dollars that have always been theoretical to the federal government, but that are very real to students, federal employees, and universities. Large scale defaults would mean lost federal jobs and significant financial problems for many universities, but it would ultimately be a zero sum game for the government.

People who owe student debts are not innocent in all this. They signed loan documents, often borrowing large sums over the course of several years. Frequently, they signed those documents without making sure they had read and understood those contracts first, relying on the word of very interested individuals that everything was on the up-and-up and that repayment would not be a problem. That’s not being a responsible consumer, and everyone should know better than to do that by the time they are a legal adult. Many student borrowers did not do their own due diligence to maximize their chances of being able to repay after graduation. When adults make poor decisions, we have to bear the consequences of those errors. However, poor decision are nowhere near the same thing as fraud or theft.

Students who cannot repay should be afforded the same protections as other debtors, especially considering that the inability to repay debts often has to do with financial problems that cannot be foreseen or that are difficult to prevent. As of 2020, the top five reasons people filed for bankruptcy, ranked from most to least common, were medical debt, job loss, excessive spending, divorce or separation, and unexpected expenses (such as rebuilding after a natural disaster) (source). Medical debt accounted for nearly two thirds of those bankruptcies. Beyond looking at personal savings, most of those causes are contingencies that cannot be taken into account when making a loan decision. They are especially hard to anticipate for young borrowers. Borrowers are not denied bankruptcy protection for federally issued loans on real estate or business either, even though the argument that their defaults “steal from taxpayers” or are malicious and premeditated should apply just as much to them as they do to students who took out federal student loans.

As a country, we are at the point of needing to make serious decisions on this issue (well past the point, actually, but better late than never). We need to acknowledge that the federal government, with the involvement of the universities and colleges, has engaged in predatory lending practices, and that it has misused its authority in order to excuse itself from its obligations as a lender and to place borrowers at a greater disadvantage than they are with other loans. It has also abused the trust of the American public by issuing loans irresponsibly to people who are unlikely to be able to repay.

As a society, we need to make sure that future students enter adulthood with the skills they need to avoid poor borrowing decisions. They need to be able to read and comprehend loan documents, know what rights they do and do not have as consumers, and know what their options are when things go sideways. Universities need to stop gouging on tuition and tailor their course offerings to match the anticipated needs of the economy. In that regard, lenders need to start taking into consideration what majors are needed, how many college educated workers the economy needs, and whether the university receiving the money is reputable when weighing loan applications.

For the most part, students don’t need loan forgiveness, they need the rights and protections afforded to other debtors, including the consequences other debtors face when they fail to repay their debts. Students also need to think before they go to college about what they want to accomplish with a degree. No one should go to university (or qualify for a student loan) without some kind of serious plan. College should not be a default next step after high school. Making sure that students seek degrees that are actually in demand could involve employers reaching agreements with universities to pay group tuition rates for employees and future employees who need additional education to advance their careers.

Borrowers of all stripes bear responsibility for making bad financial decisions, and the consequences for those decisions should be applied equally regardless of loan type or purpose. When loans go unpaid, however, the consequences need to apply to all parties to the loan contract, since all parties miscalculated the risk of the loan. It takes two to tango. The lender needs to be held just as accountable as the borrower, especially since the lender is in the position of power over the borrower and because the lender also bears responsibility to its investors. The federal government has spent decades making poor lending decisions, which not only put borrowers at a disadvantage but abused the trust of taxpayers. It is said that, when you dig yourself into a hole, the first thing you should do is stop digging. The present student loan crisis demands that the digging stop, and that can only happen if all involved parties–lenders, borrowers, and universities and colleges–are held accountable for their role in creating the circumstances in which the country finds itself.