The Brexit Landslide

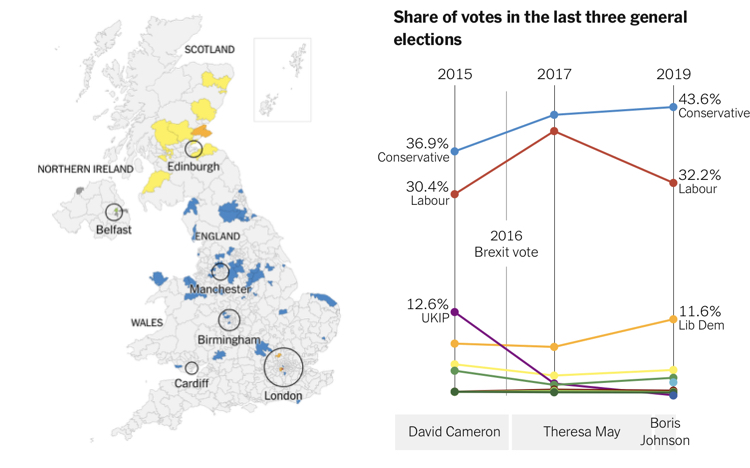

Boris Johnson has led the Conservatives (Tories) to their strongest win since 1987 on a pro-Brexit platform. Voters not only endorsed Johnson’s policies, they issued a clear rebuke to Labour and its leader, Jeremy Corbyn. Scottish and Irish nationalism is also on the rise. Prime Minister Boris Johnson will now have a broad majority and a solid mandate to enact his policies, including Brexit, government reform, and economic stimulus. With their tea and crumpets, British voters ordered a side of Brexit, hold the socialism.

Britain’s Conservative Wave

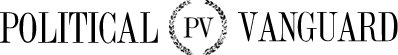

In 2016 British voters went to the polls, and 52% voted to leave the European Union, kicking off a process now called Brexit, whereby the United Kingdom will extricate itself from the gargantuan Eurocracy. Thereafter, then-Prime Minister (PM) Theresa May attempted a moderate policy, negotiating over the course of two years for a deal that would leave the UK out of the European Union but still largely economically integrated in it. This policy failed horribly and her tenure in office came to an end this summer. Her successor, Boris Johnson, was a supporter of Brexit from the beginning. His rise to No. 10 Downing Street signaled a move to a more solidly pro-Brexit policy for the Conservatives. This move has changed the party demographics of the UK and, has quite literally, redrawn the political map. Below see a side by side comparison of the 2017 election results with those of the recent 2019 general election. For information on Britain’s political system see the informational section at the end of the article.

House of Commons out of 650 seats (326 is a majority): Conservatives 365, Labour 203, Scottish National party (SNP) 48, Lib-Dems 11, Irish nationalist parties 9, others 14.

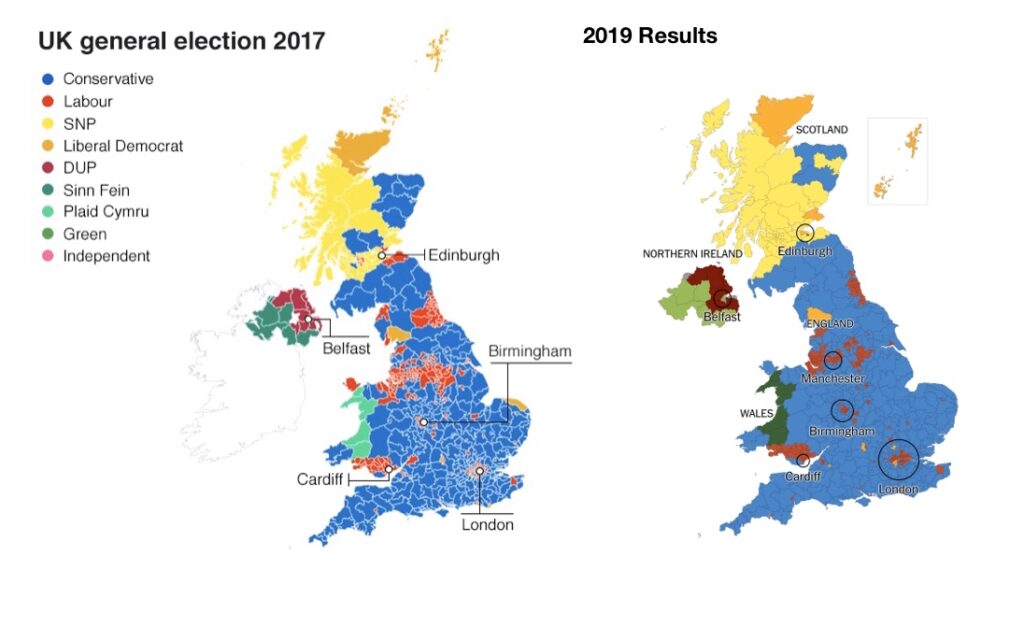

Constituencies that voted to Leave the EU in 2016 went in large numbers to the Conservatives (Tories) on the PM’s promise of “Get Brexit Done!”, bringing more working class constituencies into the Tory fold, rather than their traditional place in Labour. The map below shows the change in constituencies and the change in national vote totals amongst the parties.

Prime Minister (PM) Boris Johnson now has a clear mandate to pursue Brexit and a number of reforms he has proposed, including the building of hospitals and the hiring of more doctors and nurses for the National Health Service (NHS). With the Conservatives on 365 total constituencies, Johnson will have a strong enough majority to implement his policies freely, as he sees fit. No one faction of his party has the strength to sabotage his agenda. When it comes to Brexit, the PM says he will pass the Brexit deal he recently negotiated with the EU by the end of January. Thereafter, the Tories have set the ambitious goal of negotiating a complete trade deal with the EU by the end of 2020. On a side note, President Trump hinted at trade negotiations of his own in a congratulatory tweet on Johnson’s victory. The question now is what the PM will do with his majority and how satisfied his new voting base will be with the results in the next election scheduled in 2025 (unless Parliament calls an early election).

Labour’s Epic Defeat

Perhaps as interesting a story as the Tory victory is that of the Labour defeat. Labour suffered its worst showing since 1935. Long the butt of jokes about electoral defeats, Labour leader Michael Foot who went down to a terrific defeat in 1983 will now be let off the hook; Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn will now bear the brunt of such snide political jabs.

Corbyn’s approach to Brexit was to have his cake and eat it too. Labour’s position was that an extension of the Brexit deadline should be negotiated with the EU to afford time for a second referendum on the subject. In this epic defeat, Corbyn’s position has been proven disastrously wrong. Voters, including long-time Labour voters have clearly rebuked Corbyn on this policy. But that is not the whole story. While it is true that Labour lost votes in constituencies that had voted to leave the EU, Labour lost votes across the board—a commentary on Labour’s platform and leadership. In an election where Labour could have run to the centre politically and tried to paint the fiery Boris Johnson as a raving lunatic, Labour chose instead to launch a radically leftwing agenda for the election, a platform wholly rejected by British voters.

It is natural that Labour lost constituencies the party gained in the more recent Labour years of 1992 and 1997, but Labour lost seats this week that the party had held since 1945. One constituency, Labour had held since 1938. These losses are deep within Labour strongholds. The “Red Wall” near Manchester visible in previous elections has been shattered, for example. These losses are cutting and reflect the poor leadership and political extremism of Labour. It may take a decade or more for Labour to recover from this single election. Corbyn is a renowned socialist who praised Soviet Communism. He is also known for his antisemitism by taking a hardline anti-Israel stance, offering public support for terrorist groups like Hamas, and supporting the BDS movement. The pro-Israel Conservatives leapt at the opportunity to contrast Corbyn’s bigotry with their pro-Jewish positions. Labour never truly answered the antisemitism issue and honestly could not hope to so long as Corbyn was their Leader.

In his speech accepting reelection in his constituency, Corbyn announced he would not lead the party through another national election but that he would stay on for an indeterminate period while Labour discusses its defeat and considers its message and policies. This sounds like Corbyn wants his faction to hang on to power. Several Labour MPs called for Corbyn to quit immediately given the totality of his defeat. The pressure for such a resignation will rise in the coming days and weeks.

Rising Separatism

In Scotland, the Scottish National Party (SNP) made a comeback over its 2017 losses driving the Tories, Labour, and Lib-Dems alike from office. Scotland voted in a referendum in 2014 on the question of independence and a majority voted to remain in the United Kingdom. This win for the SNP will raise calls for another referendum on independence, but such a step remains unnecessary. SNP did not garner a majority of the votes in Scotland and SNP leader Nichola Sturgeon admitted that even among those who voted SNP in this election, many would not also vote for independence. Signaling how the SNP plans to spin their win in this election, she complained that Scots had not voted for Brexit nor had they voted for Boris Johnson, and Westminster should not be making decisions for Scotland. Exactly how the PM will answer the SNP in the coming years is not yet clear. In truth, the SNP’s comeback had more to do with the unpopularity of Labour and the Lib-Dems as national parties. At one time, Scotland was a Labour powerhouse. Nevertheless, Johnson will have to address the matter.

The PM may entertain some measure of devolution with Scotland. If Scots want greater self-determination it can be achieved without separating Scotland from the United Kingdom. Northern Ireland saw significant devolution of powers as part of the Good Friday Accord that brought an end to the longstanding conflict there. If Scotland were to become semi-autonomous, with powers similar to those of a state in the United States Federal system, Scots could take a greater role in making decisions for themselves. The SNP holds a strong minority of 62 in the Scottish Parliament, which has 129 members, 65 being a majority. If the Scottish government can govern responsibly under such an arrangement this might prove an acceptable compromise between Westminster and Edenburgh. If the Scottish Parliament proved incompetent and its leadership unpopular, Scots could opt for returning to the Westminster system in which they participate today. The question now rests upon Boris Johnson’s desk and he is not likely to make a substantial change to the current system on the results of this singular election.

Perhaps more “troubling” is the rise of nationalist parties in Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland is concerned about Brexit because it could interrupt trade with the Irish Republic or within the United Kingdom depending upon how the Brexit agreement is handled. Of the 18 seats Northern Ireland holds in Parliament, fully half are now held by Sinn Fein and the SDLP—parties that favour reunifying Northern Ireland with the Irish Republic. While the PM has a mandate for Brexit in the UK in general, this particular corner of the UK will prove nettlesome as he negotiates the minute details of the agreement. The Republic of Ireland is a member of the EU, and thus, in order to trade freely with Northern Ireland, the latter would have to be part of the EU customs union and abide by its common market rules. In order for Northern Ireland to trade freely with the UK after Brexit, however, they must not abide by EU rules but by the laws and policies of the UK. This question threatens to reignite the Troubles, a period of violence between Irish Republicans and Unionists/Loyalists that festered in Northern Ireland in the late 20th Century. With great effort the conflict ended with the Good Friday Accords negotiated in 1998, with significant assistance from the Untied States, a neutral party. One certainly hopes Northern Ireland does not descend back into violence.

The election results have given Prime Minister Boris Johnson a solid majority and a mandate to lead. It has also beset him the many headaches of leadership. It is incumbent upon him to take full measure of this opportunity and accomplish something of what he has promised to deliver. The epic defeat of Labour and its relative insignificance going forward will pose a serious problem for the party faithful as they attempt to rebuild their movement and their popularity—no small challenge. Overall, Brits seem to have taken a sigh of relief. They now have an end to the period of uncertainty as to how the country would go forward. Now they can rest assured it will go forward to Brexit and reforms aimed at better government services and a stronger economy.

The British Political System

In the 19th Century, Great Britain, now styled the United Kingdom, evolved from a system in which the monarch appointed the Prime Minister and cabinet to enact his policies, into the first truly parliamentary system, so named for the British Parliament or legislative branch. In this system, as described by Walter Bagehot, a contemporary commentator on the British Constitution, a parliamentary system is one in which voters choose the executive branch by means of indirect election by an electoral body similar to the American Electoral College. This electoral body is the House of Commons, the lower house of the British Parliament, which doubles as the national legislative body. The House of Commons elects a “government” made up of a Prime Minister and his or her cabinet ministers. This government serves at the pleasure of the House and can be removed at any time by a vote of no confidence. If a majority of the House votes no confidence in the Prime Minister, the PM loses his or her office and a new leader is chosen. This is very distinct from the American system, wherein we elect our President through an indirect election by the Electoral College, the President serves for four years, and cannot be unelected until the voters choose a new electoral college. The state by state winner-takes-all system for choosing the electors in our electoral college system confuses the matter a little.

We are all too familiar with the nigh impossible process of impeachment of the sitting President by the House of Representatives. The President is then tried by the Senate, wherein the commission of the crime or crimes must be firmly established, and a two-thirds vote is required to remove the President. Removal has never happened in the 230-odd years since the US Constitution went into effect; and is unlikely to happen in the near future.

The House of Commons comprises 650 seats, each representing a geographic district called a “constituency,” which are drawn to be approximately equal in population and represent all jurisdictions within the United Kingdom: England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Each constituency elects a Member of Parliament (MP) who has won the greatest number of votes cast within the constituency (first past the post). There is no priority voting, instant runoff, or runoff election. Thus, winning approximately 43% of the national popular vote can install a very large majority like the one that has just been chosen. The House of Representatives in the United States is similar to the House of Commons in the UK, upon which it was originally modeled. However, the House of Representatives is merely a legislative body and does not have any role in choosing the executive unless none of the candidates wins a majority of the electoral votes.

A party in the Commons needs 326 seats, half plus one, to hold a majority of the House and to choose a Prime Minister of their choice. On rare occasions, two or more parties form a coalition government when no party holds a majority. This is very rare in the British system, unlike multiparty proportional systems like those of Germany and many European countries. In the 2010 and 2017 elections the Conservatives fell short of a majority of seats and had to seek coalitions with smaller parties in order to govern. Elections are fixed at five year intervals by the Fixed Term Parliament Act of 2011, which is slated to be revised in the coming years, although early elections can be held if 2/3rds of the House of Commons votes to call them. The Queen used to have the power to dissolve Parliament and call for new elections, which was done upon the request of the Prime Minister, but the last vestiges of this power were repealed in 2011.