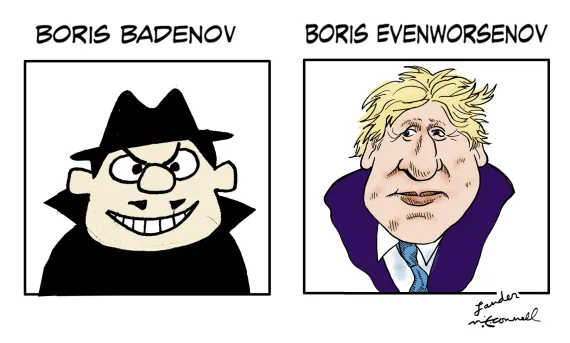

Boris Bad Enough

Boris Johnson has resigned as Prime Minister amid political scandal and directionless leadership. The contest to succeed him has begun. Who will be the next leader of the Conservatives (Tories) and what direction will they take? Britons are suffering terrible economic hardship, what are the Tories going to do about it?

In a recent article Andrew Neil, Scottish journalist and commentator, offered a perspicacious postmortem of Boris Johnson’s Premiership. Johnson came to office surrounded by excitement and full of potential, now he is leaving office a terrific disappointment to his erstwhile supporters. Following the Brexit referendum in 2016, then Prime Minister David Cameron departed the leadership. He could not lead the United Kingdom (UK) out of the European Union (EU). Theresa May rose to the leadership in the wake of Cameron’s departure seeking some kind of compromise on Brexit: could the UK be half in and half out of the international economic union come supra-European state? Alas, all of her negotiations proved unacceptable both to the European Council and to the British Parliament. Her election debacle in 2017 then brought the Tories just below an absolute majority of the House of Commons. It was soon clear that Britain needed the leadership of a Brexiteer. Johnson’s anointment as party leader seemed auspicious to that end.

Upon assuming the Premiership, Johnson was quickly embroiled in the infighting of the fractious Tory Party just-minority. He decided to push for a “hard Brexit” whereby the UK would simply depart the European Union (EU) without any prior agreement with that organization. This presents some problems for Ireland, wherein northern Ireland (most of County Ulster) remains highly economically intertwined with the Irish Republic, which remains a part of the EU. Aside from this technical challenge, the UK managed Brexit with some ease. Britons were excited about the prospect of reasserting control over their own fate. Britain is free to choose her own path, and certainly the path of prosperity! Calling for early elections once again, in December 2019, Boris Johnson rode this wave of hope for prosperity and independence to one of the greatest electoral victories in recent history. The opposition Labour Party imploded against a wave of populist support for Johnson and the potential his leadership engendered. The Tories gained 48 seats in parts of the country that were formerly solid Labour fortresses, even as Labour lost 60 seats, 12 to the Scottish National Party (SNP).

At that moment, a glimmer of hope shone brightly that the UK might rise to new heights of prosperity something like the heady days late in the Thatcher era when the British economy was strong and resilient. That glimmer glinted quickly before darkness resumed. During the Wuhan Virus (COVID) crisis, Johnson like so many other leaders, took to the totalitarian approach to the virus: lock downs. Never mind the fact that attempts at quarantine diseases always fail, that there is no evidence that lock downs would actually reduce mortality (in fact they had no effect), and never mind the terrible social and economic strain they were to cause. Now, the consequences are setting in: rampant inflation, supply chain failures, and food shortages. Anyone familiar with the history of totalitarian regimes could have predicted these results: even mild dictatorship has similar results to untempered absolutism. So, as was the case in the Soviet Union and as is the case in Venezuela today, the British economy has suffered terrific setbacks. Against the background of these lock downs, it seems as ordinary Britons were stuck in their homes unable to visit elderly relatives dying at hospital, Boris and his compatriots were holding parties. A scandal that rocked his administration and contributed to his downfall.

Johnson could find no answer to the scandalous parties he attended that will haunt his legacy, just as he has no answer to the economic challenges the UK faces. He has no roadmap for economic recovery: no plan to combat inflation and price hikes, no plan to restore the labor market, no plan to cut government spending in order to curtail inflation. Quite the opposite, Johnson has been spending wildly, raising taxes, and expanding bureaucratic control. It seems Boris has it all wrong. Once the champion of the Conservative rank and file, the party base, he has become their pariah. A political survivor, it seemed Johnson might even weather the scandal if only he could somehow turn about the bad economic news. Alas, this was not to be the case: Boris faced a trickle of low level resignations from his cabinet until several high ranking officials departed. Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor is looked upon as the #2 in the cabinet, resigned in protest of the government last week forcing Boris to call it quits.

As Andrew Neil notes, the United Kingdom had the potential post-Brexit to become the Texas of Europe: a paradise of low taxes, competitive corporate taxes, and of economic liberalism (free market policies). Yet, this dream has not materialized. Long-time Brexiteer David Davis recently gave an interview, again with Mr. Neil, in which he could not point to a single benefit of Brexit for ordinary Britons. Aside from the specious argument that the UK now has restored democracy, the ability for British voters to chart the course of their own government without interference from Brussels, there have not been any perceivable benefits. Surely, Mr. Johnson had a plan for the UK post-Brexit? Mr. Johnson may be a victim of his own personality flaws as many who have worked with him in the past say he is a brilliant and capable man beset by his own disorganization and unable to trust competent people around him. Something like Richard Nixon falling prey to his own paranoid delusions. Now that Mr. Johnson is departing, many questions remain for the Tories.

Post-Johnson Conservatives

So who will lead the Tories and what will their direction be? The BBC lines up five potential successors to Boris, with three more in the wings looking for a chance to join the leaders. These candidates they describe here. Three candidates at the top of the list warrant some description. The aforementioned Rishi Sunak is the former Chancellor of the Exchequer (not unlike the Secretary of the Treasury) whose resignation signaled the end of Boris Johnson’s Premiership. Sunak has been the subject of a scandal concerning his wife’s taxes and has also participated in breaches of the lock downs. He has charted an establishment course shying away from tax cuts until the government’s finances improve and adopting fairly mainstream positions. He may be a favorite of insiders, but Tory rank and file are rather on the outs with the insiders at the moment.

Liz Truss, on the other hand, has set out to distinguish herself early in the process. She has embraced immediate tax cuts and the end to a planned national insurance rate hike. She has lately been the Foreign Secretary, akin to the US Secretary of State, and has secured the support of many of Johnson’s inner circle. Truss was at one time a member of the UK’s third party the Lib-Dems and may struggle to earn the trust of the rank and file.

Penny Mordaunt is a very interesting candidate: Penny has been serving as Trade Secretary for the past year and was the first woman to serve as Secretary of Defence, which office she held briefly at the end of the Theresa May premiership. Mordaunt has a more fascinating background having worked within the Conservative Party for decades and even working on US president George W. Bush’s two presidential campaigns. She has promised immediate tax cuts, especially on the VAT (sales taxes) and on fuel. Mordaunt has also promised raising deductions for taxes on the middle class. While not precisely the favorite of the insiders, she has amassed an incredible list of backers early in her candidacy including long-time anti-EU Tory stalwart David Davis and recent leadership challenger Andrea Leadsom. Davis was the runner up to David Cameron for the leadership in the late aughts and Leadsom was the final challenger to Theresa May in 2016. Mordaunt has crashed into the top three from relative obscurity in part, because she is a long-time Brexiteer. Many other Tory party members previously supported Remain before choosing the Brexit side only after that proved to be the more popular course.

Each of the three top candidates brings much to the table. Sunak aside, they seem to be charting a familiar Thatcherite course. It seems free market economics and economic liberalism have become the popular approach once again as the Tories seek to recover from the Johnson scandal and revive their party’s sinking public standings.

Electoral Outlook

In the 1990’s John Major was able to recover quickly from Margret Thatcher’s ignominious ouster from Number 10. He held the cabinet together as the Tories charted a more establishment course away from Thatcher’s liberal economic policies. In 1992, despite losing a significant number of seats to the Labour opposition, Major was able to hold on to the majority in ’92 and for a time it seemed he might even be able to drag the Tories through the 1997 election. Tony Blair crushed those hopes when he took over the Labour Party and began the era of “New Labour.” Marrying the traditional left wing social policies of the Labour movement to Thatcher’s economic policies, he was able to bring Labour careening into the majority in 1997. For the next ten years, Britain prospered under centre-left leadership. Blair’s ouster by his own party in 2007 led to Labour’s ultimate downfall in 2010.

Andrew Neil captures the moment well when he notes that today’s Labour leader Keir Starmer is no Tony Blair. Perhaps the salvation of the Conservative Party is that if they can just chart a better course, especially on the economy, voters may reward them in 2024 when new elections must be held. Even as voters will not have had time to perceive many of the benefits of any such change of course between now and then. Perhaps greater salvation still, comes from the Scottish National Party (SNP) whose takeover of Scottish constituencies in Parliament has hamstrung Labour. Not long ago, Labour could count on forty-odd seats from Scotland to beef up their seats in England. Of the approximately 650 seats in the House of Commons, 326 constituting a majority, Labour would now have to be able to gain 134 seats in England to reach a majority. This would require regaining their lost seats and garnering many seats in Tory strongholds. This result is unlikely.

If the Tories can recover quickly from this crisis, restore trust in the nation’s leadership, and chart a new course on the economy, they may yet salvage their majority at the next election. Even if they cannot accomplish all of these goals, the Tories are likely to win for losing between Starmer’s lack of charisma and Labour’s inability to win the needed seats. Snatching victory from the jaws of defeat may well be all the Tories can hope for. If only Boris Johnson had lived up to some of his potential and led the Tories to better results…